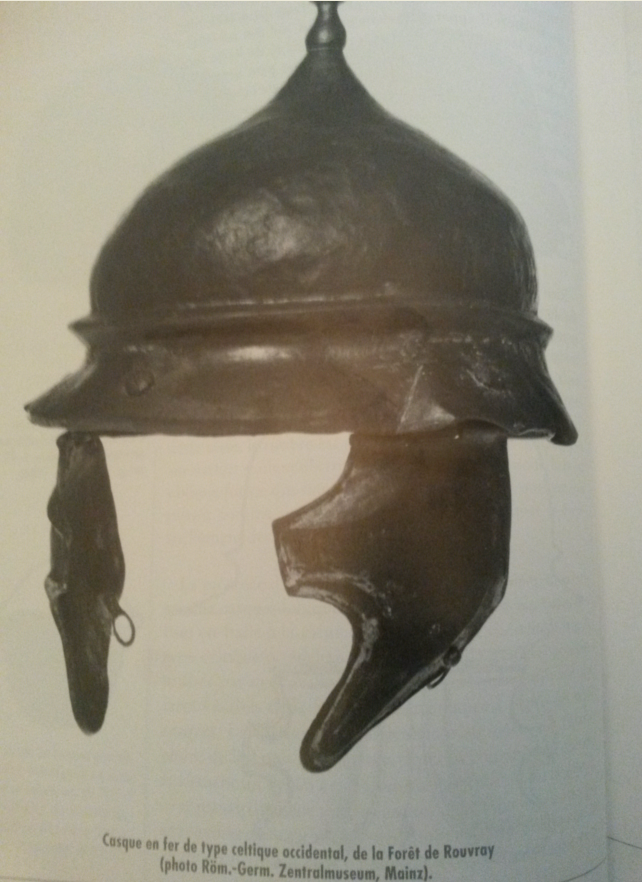

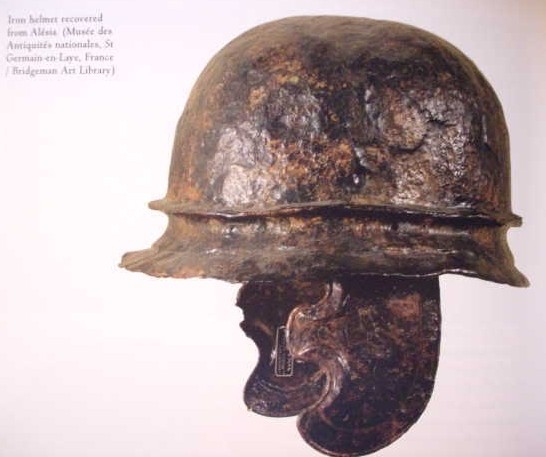

The settlements at the time remain little-known, and there is scant information about artisanal output. Between the end of the fourth and end of the third centuries BC, ironwork was already highly developed at Sajopetri in Hungary as well as at Manching in Bavaria, Aulnat in Auvergne, and Lacoste in Gironde. Even so, given the available information, it may be supposed that production was relatively loosely organized across various sites. Funerary and religious contexts provide the bulk of documents. For an idea of the scale of standardization, it is sufficient to examine the distribution not just of personal items (for example, the copper alloy fibulae from Duchcov or Munsingen, or short swords that have scabbards with openwork and rounded chape ends, which are typical series from the last two-thirds of the fourth century BC), but also the sets of weapons, combining a sword (complete with scabbard and suspension system), a spear, and personal shields, which have been found in lands separated by several hundreds or thousands of kilometers. The patterns, more symbolic than ornamental, in an escutcheon arrangement — such as zoomorphic lyres on a textured background — that were reproduced identically on certain swords of similar shape and design found in France (Champagne, Languedoc), northern Italy, Hungary, and even Britain also give another idea of the scale of standardization. Technological innovations also attest to the vitality of those living north of the Alps. Here too, inasmuch as they cannot be separated from the warrior elites, armaments benefitted the most from these advancements. The sword, carried on the right at waist-level, denoted this excellence in war throughout the Second Iron Age. The scabbard, which both protected and decorated it, was a composite object consisting of two plates held together with an end chape, along with a means of suspension attached at the back and various support pieces. Inseparable from the sword, it was custom-made in order to protect the blade effectively by keeping movement of the sword edges to a minimum. It could also be completely taken apart for maintenance and repair. An initial phase (La Tene A, or the fifth century BC) characterized by output with relatively strong regional characteristics despite certain commonalities, gave way to a phase dominated by the trend toward standardization. This shift, which can be observed from the start of the fourth century BC, went hand in hand with technological advancements. While blacksmiths had already amassed four centuries of experience, it was not until the fifth century that they began producing sheets of metal to make scabbards, which replaced sheaths formerly made of wood or leather. Toward the end of the century, craftsmen abandoned the use of bronze for sheet metal, which was common throughout the fifth century BC, in favor of iron as they became adept at making sheets that were sufficiently thin (only several tenths of a millimeter thick) and hard wearing. Bronze was used only for decorative purposes, in the form of often very delicate bronze leaf covering the iron plate. It was only in the British Isles that bronze continued to be employed up until Romanization. On the continent, bronze only resurfaced during the second century, alone or in combination with iron. Sheet iron was difficult to work with: during the initial phase in the fifth century BC, artisans often proceeded via welding and riveting (Cortrat), a technique inspired by pot-making (as in the Celtic jugs with tubular spouts obtained by riveting together thin sheets of bronze). For populations in a large part of Middle Europe, the preference for iron left a lasting impression on the history of weapons. This was accompanied by another innovation connected to the suspension system (comprising the scabbard’s suspension device or hasp and belt) and the need to create a fastening that could withstand the impact of rapid movement (the Celtic warriors of the day were primarily foot-soldiers). In the third century BC, the addition of bronze or iron chains dramatically changed the traditional leather belt with hoops and hooks that had been used since the fifth century. The concept was commented on by ancient writers, such as Diodorus Siculus at the dawn of our own age. In the new system, two chains of different sizes attached to the scabbard’s suspension piece were now joined to the leather belt, a short section running forward on the right-hand side and a longer section encircling the body around back but attached at the front. At the start of the third century BC, this original system emerged simultaneously not only in western and eastern Europe but also in Italy. The innovation and formal variety of the initial phase was soon reduced to a few basic concepts (two or three in each generation for about a century). The heavy, cumbersome chains from the beginning of Middle La Tene (the second quarter of the third century BC) became more delicate and developed toward greater comfort. The use of semi-rigid belts was finally abandoned just before the end of the third century BC, when cavalry was being established. The return to simple leather belts with hoops and hooks brought this interlude of barely a hundred years to a close. Largely made of perishable materials, the oval Celtic shield made its appearance at the dawn of the third century BC, when the use of metal umbos designed to provide the hand-grip with better protection became widespread. The first attempts at bivalve coverings gave way to transverse band-shaped bosses and ultimately, from the end of the second century BC, to circular designs that implied the central spine had disappeared. The helmets worn during the second half of the fifth century BC by certain warriors found buried on their two-wheeled chariots did not subsequently become part of military equipment, except in the southeastern alpine area and Balkan Europe.

Source:

https://www.cairn-int.info/article-E_ANNA_672_0295--the-golden-age-of-the-celtic-aristocracy.htm