LtSpearing

Sergeant Knight

Hey budding NW community,

I've been seeing a lot of regiments being made, especially the ones with rich, unique, and interesting historical backgrounds. Some, interestingly enough, I have never heard of or seen, so in an effort to pool together some cool little information about each regiment, I'm making this thread.

Some guidelines for a post:

Post your Regiment's name, Also post it's Regimental colours. Preferably post the ones that were around during the Napoleonic Wars, so we can get deeper into the feel of the period, but if you can only find colours that were sewn after, then that's alright too. Post a quick tiddle of info as well, such as an interesting event, or a specific action they performed that marked them as note-worthy. ONLY post an event or piece of information that had to do with the Napoleonic era, with a date capped at 1821 (Napoleon's death) and no earlier than 1760, so we can keep these histories coherent.

But let's keep some things off the thread:

I want to keep this thread on a historical-basis only; No recruiting, no "Join my reg" ads or what-not. Just post the real-deal.

With such a broad community, I don't doubt in the least we will see some truly epic pieces of information pop up.

I'll update the main post every now and then with spoilers, so you can basically use this thread as a quick reference with every regiment and so forth.

REGIMENTAL HISTORY LIST

I've been seeing a lot of regiments being made, especially the ones with rich, unique, and interesting historical backgrounds. Some, interestingly enough, I have never heard of or seen, so in an effort to pool together some cool little information about each regiment, I'm making this thread.

Some guidelines for a post:

Post your Regiment's name, Also post it's Regimental colours. Preferably post the ones that were around during the Napoleonic Wars, so we can get deeper into the feel of the period, but if you can only find colours that were sewn after, then that's alright too. Post a quick tiddle of info as well, such as an interesting event, or a specific action they performed that marked them as note-worthy. ONLY post an event or piece of information that had to do with the Napoleonic era, with a date capped at 1821 (Napoleon's death) and no earlier than 1760, so we can keep these histories coherent.

But let's keep some things off the thread:

I want to keep this thread on a historical-basis only; No recruiting, no "Join my reg" ads or what-not. Just post the real-deal.

With such a broad community, I don't doubt in the least we will see some truly epic pieces of information pop up.

I'll update the main post every now and then with spoilers, so you can basically use this thread as a quick reference with every regiment and so forth.

REGIMENTAL HISTORY LIST

The 24th Warwickshire Regiment of Foot

History

History; The 92nd Gordon Highlanders at Quatre Bras and the death of the gallant John Cameron of Fassifern

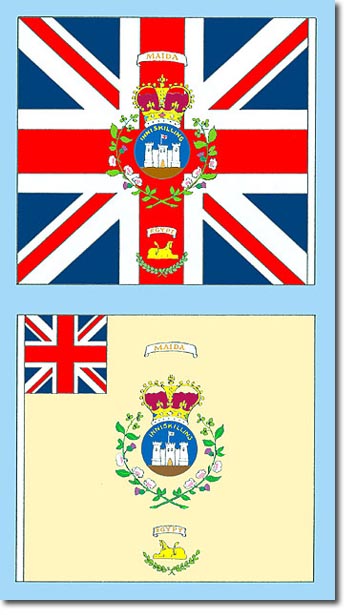

27th (Enniskillen) Regiment of Foot

"The Skins"

Written by Lordnred from his own personal Research on the Internet, in books, and of course at the Regimental Museum in Enniskillen:

Follow the same format, and I hope to see some interesting info on other reg's

Remember: Keep it short, sweet, and provide a battle or two if you can. Don't post anything about recruiting though, let's keep this totally historical.

If you feel like there is another regiment you want to post about, but it isn't an actual regiment in the community, that's also fine. Just provide some info

I'll be organizing a list as more regiments post.

History

Before the Napoleonic wars, the 24th can be considered generally unlucky, as it was present at a number of military blunders by British commanders during the American Revolution, and so forth. But after that, it was considered one of the hardest-fighting regiments during the Napoleonic Wars. One example can be easily drawn from the Battle of Talavera, where the 24th was ensconced in such a fierce firefight with a number of French forces, it suffered some of the heaviest casualties of the battle. After that, it was given over to the First Gurkha war, which set it's tradition to be posted in colonial wars.

The regiment was formed as Sir Edward Dering's Regiment of Foot in 1689, becoming known, like other regiments, by the names of its subsequent colonels. It became the 24th Regiment of Foot in 1751, having been deemed 24th in the infantry order of precedence since 1747. In 1782 it became the 24th (The 2nd Warwickshire) Regiment of Foot. The 1st Warwickshires were the 6th (1st Warwickshire) Regiment of Foot.

In 1741, during the War of Jenkin's Ear, the regiment was part of the amphibious expedition to the Caribbean and participated in the disastrous British defeat at the battle of Cartagena de Indias.

In 1756, during the Seven Years War, the regiment was part of the garrison on Minorca and surrendered to the French on June 28.

In 1758, during the Seven Years War, the regiment was part of the amphibious expedition against, or descent on, the coast of France and participated in the disastrous British defeat at the battle of Saint Cast.

In 1776 the regiment was sent to Quebec where it subsequently fought American rebels who had invaded the province during their War of Independence. The regiment was part of the 5,000 British and Hessian force, under the command of Gen. John Burgoyne, that surrendered to the American rebels in the 1777 Saratoga Campaign and remained imprisoned until 1783.

In 1804 a 2nd Battalion was raised but its life was relatively short when it was disbanded in 1814, having seen service in the Peninsular War.

In 1810 the vast majority of the 1st Battalion was captured at sea by the French; they were released the following year. They had been on the East Indiamen Astell, Ceylon and Windham when a French frigate squadron captured the last two at the Action of 3 July 1810 near the Comoros Islands.

In 1814 the 1st Battalion took part in The Gurkha War, which saw the British and the Gurkhas gain mutual respect. After the war, the British began recruiting Gurkhas,who became part of the British Indian Army. When India became independent in 1947, four Gurkha regiments transferred to the British Army.

The regiment was formed as Sir Edward Dering's Regiment of Foot in 1689, becoming known, like other regiments, by the names of its subsequent colonels. It became the 24th Regiment of Foot in 1751, having been deemed 24th in the infantry order of precedence since 1747. In 1782 it became the 24th (The 2nd Warwickshire) Regiment of Foot. The 1st Warwickshires were the 6th (1st Warwickshire) Regiment of Foot.

In 1741, during the War of Jenkin's Ear, the regiment was part of the amphibious expedition to the Caribbean and participated in the disastrous British defeat at the battle of Cartagena de Indias.

In 1756, during the Seven Years War, the regiment was part of the garrison on Minorca and surrendered to the French on June 28.

In 1758, during the Seven Years War, the regiment was part of the amphibious expedition against, or descent on, the coast of France and participated in the disastrous British defeat at the battle of Saint Cast.

In 1776 the regiment was sent to Quebec where it subsequently fought American rebels who had invaded the province during their War of Independence. The regiment was part of the 5,000 British and Hessian force, under the command of Gen. John Burgoyne, that surrendered to the American rebels in the 1777 Saratoga Campaign and remained imprisoned until 1783.

In 1804 a 2nd Battalion was raised but its life was relatively short when it was disbanded in 1814, having seen service in the Peninsular War.

In 1810 the vast majority of the 1st Battalion was captured at sea by the French; they were released the following year. They had been on the East Indiamen Astell, Ceylon and Windham when a French frigate squadron captured the last two at the Action of 3 July 1810 near the Comoros Islands.

In 1814 the 1st Battalion took part in The Gurkha War, which saw the British and the Gurkhas gain mutual respect. After the war, the British began recruiting Gurkhas,who became part of the British Indian Army. When India became independent in 1947, four Gurkha regiments transferred to the British Army.

21e Regiment d'Infanterie de Ligne

The 21ème Regiment d'Infanterie is one of the oldest regiments in the World. It was raised in Lorraine in 1598 by Henri de Vaubecourt at the time when Henri of Navarre became King Henry IV of France. It continued as a regiment of the Monarchy under the name of its Colonel until it became the Regiment Guyenne in 1762.

It was not until the French Revolution that it was known as the 21eme Demi-Brigade de Ligne. The regiment served in Germany in 1793 and by the mid 1790's was in the Armme d'Italie. The 2leme was involved in action at Laona in 1796 and also Montenotee, Millesimo, Dego and the bridge at Lodi. It was at Lodi where Grenadiers of the Regiment charged over the bridge under constant fire shouting "Vive la Republique!" overthrowing the Austrian defenders and capturing their artillery.

In 1799 the regiment saw further action at Verona, Magano, Trebbia and most notably the Battle of Novi. It was here that Sergeant-Major Jean Georges Pauly, cut off by a body of Russian Cavalry was called upon to surrender. Replying Je Passe Quand Même he rallied a handful of men and forced his way back to the regiment using musket butt and bayonet killing or wounding more than 40 Russians in the process.

The regiment was designated the 21eme Regiment d' Infanterie de Ligne in 1803. In 1804 it formed part of the Armee d' Angleterre when the concept of the Grande Armee was first created by Napoleon Bonaparte. In 1805 the regiment marched under Marshal Louis Nicoholas Davout as part of the 3eme Corp d' Armee to fight the combined might of Austria and Russia at Austerlitz.

In 1806 Davout's Corps found itself facing the main Prussian army under the Duke of Brunswick at Auerstadt, whilst Napoleon was defeating what he believed to be the main army at Jena. The 21eme defended the village of Hassenhausen in the centre of the French line. Corporal Boutloup of the Voltigeur company, along with six men, took a Prussian gun and caisson and turned it on the Prussians. These men, having killed the gun crew, manned the cannon for over half an hour until ammunition was exhausted. Losses were heavy but the three divisions of the 3eme Corp became famous through the Armee as "Les Trois Immortelles".

The 21eme saw further action at Custrun, Pultusk and Eylau and later still at Eckmul and Wargram. It was at Custrin, a single company bluffed the fortress into surrendering and took 4,000 Prussian prisoners.

In 1812 the regiment was once again with Davout as part of the crack ler Corp. The 21eme now comprised 6 battalions (4 veteran battalions, the depot battalion and the new 6th battalion led by graduates from St Cyr and volunteers from the Garde.) It fought at Smolensk, Valoutina Gora and Borodino in the bitter Russian campaign. The regiment then faced the winter retreat from Moscow. From a strength of over 4200, only 92 remained in arms by the 1st of February 1813.

The 21eme was later reformed in the same year and saw action including the battle of Dresden. It was here the regiment was left behind while Napoleon moved back to Leipzig. It fought at Hellendorf where Lieutenant Doignon and the Grenadier company took some 70 Russian prisoners.

Inevitably, the 21eme passed into captivity at Dresden.

In 1814 the regiment was reformed from the depots in France and fought the British army for the very first time at Bergen op Zoom in the Netherlands. It was here that the Colour of the Foot Guards was taken. (Now on display at the Invalides in Paris)

Now following the Emperor's abdication the 21e Regiment de Ligne continued as a reluctant regiment of the monarchy.

Napoleons return from exile in 1815 marked the start of a campaign that was to become known as the 100 Days. He re-instated himself as Emperor of France, banished the Bourbons and brought back the tricolour flag. As the storm clouds gathered over Europe his imperial army formed up below the eagles once again.

During this period the 21eme formed part of the 3eme Division in the 1er Corp commanded by the Compte Drouet d' Erlon. The regiment missed both actions at Ligny and Quartre Bras to the confusion of orders between Napoleon and Marshal Ney. Two days later they formed part of the French right wing on the field of Waterloo. Here the 21eme took part in the early stages of the baffle during the advance on the Allied centre. With shouts of "Vive L' Empereuer!" they descended into the valley under the fiery vault of French and English shells which arched over their heads. With drums beating the advance in massed formation up the slopes of Mont Saint Jean to meet Wellington's army. Before the crest D'Erlon's Corp were stopped by a hedge, in front of which the leading ranks were forced to deploy. Here they were surprised by the Highlanders and became involved in a fierce melee. This was only broken as the French heavy cavalry charge by Wellington's Union Brigade. The 21eme retired as best it could.

The regiment was later involved in the capture of the farmhouse of La Haye Saint but never fully recovered from this onslaught. Following the arrival of the Prussians and defeat of the Old Guard the day was lost. The remnants of the regiment regrouped at Laon but Waterloo was the last baffle in the Napoleonic Wars and spelt the end of the era in Europe.

The 21eme have continued active service over the years in Algeria, Italy, the Crimea (allied to the English!), the Franco-Prussian War, the Great War and World War II.

It was not until the French Revolution that it was known as the 21eme Demi-Brigade de Ligne. The regiment served in Germany in 1793 and by the mid 1790's was in the Armme d'Italie. The 2leme was involved in action at Laona in 1796 and also Montenotee, Millesimo, Dego and the bridge at Lodi. It was at Lodi where Grenadiers of the Regiment charged over the bridge under constant fire shouting "Vive la Republique!" overthrowing the Austrian defenders and capturing their artillery.

In 1799 the regiment saw further action at Verona, Magano, Trebbia and most notably the Battle of Novi. It was here that Sergeant-Major Jean Georges Pauly, cut off by a body of Russian Cavalry was called upon to surrender. Replying Je Passe Quand Même he rallied a handful of men and forced his way back to the regiment using musket butt and bayonet killing or wounding more than 40 Russians in the process.

The regiment was designated the 21eme Regiment d' Infanterie de Ligne in 1803. In 1804 it formed part of the Armee d' Angleterre when the concept of the Grande Armee was first created by Napoleon Bonaparte. In 1805 the regiment marched under Marshal Louis Nicoholas Davout as part of the 3eme Corp d' Armee to fight the combined might of Austria and Russia at Austerlitz.

In 1806 Davout's Corps found itself facing the main Prussian army under the Duke of Brunswick at Auerstadt, whilst Napoleon was defeating what he believed to be the main army at Jena. The 21eme defended the village of Hassenhausen in the centre of the French line. Corporal Boutloup of the Voltigeur company, along with six men, took a Prussian gun and caisson and turned it on the Prussians. These men, having killed the gun crew, manned the cannon for over half an hour until ammunition was exhausted. Losses were heavy but the three divisions of the 3eme Corp became famous through the Armee as "Les Trois Immortelles".

The 21eme saw further action at Custrun, Pultusk and Eylau and later still at Eckmul and Wargram. It was at Custrin, a single company bluffed the fortress into surrendering and took 4,000 Prussian prisoners.

In 1812 the regiment was once again with Davout as part of the crack ler Corp. The 21eme now comprised 6 battalions (4 veteran battalions, the depot battalion and the new 6th battalion led by graduates from St Cyr and volunteers from the Garde.) It fought at Smolensk, Valoutina Gora and Borodino in the bitter Russian campaign. The regiment then faced the winter retreat from Moscow. From a strength of over 4200, only 92 remained in arms by the 1st of February 1813.

The 21eme was later reformed in the same year and saw action including the battle of Dresden. It was here the regiment was left behind while Napoleon moved back to Leipzig. It fought at Hellendorf where Lieutenant Doignon and the Grenadier company took some 70 Russian prisoners.

Inevitably, the 21eme passed into captivity at Dresden.

In 1814 the regiment was reformed from the depots in France and fought the British army for the very first time at Bergen op Zoom in the Netherlands. It was here that the Colour of the Foot Guards was taken. (Now on display at the Invalides in Paris)

Now following the Emperor's abdication the 21e Regiment de Ligne continued as a reluctant regiment of the monarchy.

Napoleons return from exile in 1815 marked the start of a campaign that was to become known as the 100 Days. He re-instated himself as Emperor of France, banished the Bourbons and brought back the tricolour flag. As the storm clouds gathered over Europe his imperial army formed up below the eagles once again.

During this period the 21eme formed part of the 3eme Division in the 1er Corp commanded by the Compte Drouet d' Erlon. The regiment missed both actions at Ligny and Quartre Bras to the confusion of orders between Napoleon and Marshal Ney. Two days later they formed part of the French right wing on the field of Waterloo. Here the 21eme took part in the early stages of the baffle during the advance on the Allied centre. With shouts of "Vive L' Empereuer!" they descended into the valley under the fiery vault of French and English shells which arched over their heads. With drums beating the advance in massed formation up the slopes of Mont Saint Jean to meet Wellington's army. Before the crest D'Erlon's Corp were stopped by a hedge, in front of which the leading ranks were forced to deploy. Here they were surprised by the Highlanders and became involved in a fierce melee. This was only broken as the French heavy cavalry charge by Wellington's Union Brigade. The 21eme retired as best it could.

The regiment was later involved in the capture of the farmhouse of La Haye Saint but never fully recovered from this onslaught. Following the arrival of the Prussians and defeat of the Old Guard the day was lost. The remnants of the regiment regrouped at Laon but Waterloo was the last baffle in the Napoleonic Wars and spelt the end of the era in Europe.

The 21eme have continued active service over the years in Algeria, Italy, the Crimea (allied to the English!), the Franco-Prussian War, the Great War and World War II.

1er Regiment de Grenadiers a-pied de la Garde Imperiale

History(WARNING: Theres a lot of it)

The 1er was apart of the Old Guard named: 1er Régiment de Grenadiers-à-Pied de la Garde Imperiale under the 1st Division.

There were in that Division 3 grenadier regiments, and 2 chasseur regiments.

As we all know, this is how a regular grenadier looks.

If you´ve noticed there is a white embroidered grenade, on the top of their cap. That first became official in 1807 after the peace in Tilsit where it before was a white cross.

After Napoleon abdicated in 1814, and Louis the XVIII was restored, he replaced the grenadiers eagle with a royal plate. When Napoleon returned for his 100 days, they didn´t have time to replace it, so they put a tricolor on it. So basiclly we didn´t have the eagle plate at waterloo.

Here you see a picture of a grenadier with a normal hat on instead of the "Bonnet de Poil" (bearskin hat). The guard may have been proud of it, but marching with it was horrible, so they used that hat instead when they weren´t at ceremonies or in battle.

The Grenadiers would usually be on the march with full equipment, which would be around 32 pounds. Sometimes they would be ordered to march over 140 to 180 km in 36 to 76 hours.

A linesmen once made the remark: "Emperor is using our legs more than our bayonets to make war."

However, out of "fatherly love" towards his children´s favorite, the Emperor had put carts avalible to transport his grenadiers, while the other line regiment had to walk.

Typically, Colonels of any regiment within the Old Guard could have the rank of "Brigadier General". Like you see above.

The 1er Grenadiers musicians were not in green jackets, like you see in Mount&Musket, they were wearing standard uniforms with golden trimmed robes and fine bronze plates on their shoulders.

The 1er Grenadiers were part of Napoleon's Imperial Guard (which was an army in itself, having cavalry, artillery and infantry at its peak), which was in turn part of Napoleon's Grande Armee, the massive fighting force Napoleon used to smash Europe, which ultimately was mostly killed in the snows of Russia. Unfortunately, almost all of the initial Old Guard were dead by the time Napoleon had retreated from Russia.

The 1er Grenadiers, I'm sure you all know, were known as Les Grognards (the grumblers), reputed to air any complaints they had to their commanders without any hesitation. The most common grumble they would have is that they were not committed to battle enough, only being committed when there was dire need for it. Other regiments in the guard were committed at times, but the treasured 1er saw little action. However, attributed to the action the Old Guard did see, was the fact that they were reputedly undefeated. The Guard was far from useless however, in fact saving Napoleon's life at one point, when he was surrounded in a church at the Battle of Eylau, with only his advisers to defend him! They managed to hold out for long enough against the Russians before some battalions of the Guard arrived to drive them off.

The 1er Grenadiers and 1er Chasseurs were the best selection of men by far of the Old Guard, and people may say that the Old Guard routed at Waterloo, and call us cowards, but it was the rest of the Imperial Guard that infamously routed, a few battalions of surviving Old Guard -the 1er being part of them- standing their ground.

Also, it is true that the Old Guard were not that old, you actually HAD to be under 35 to join it! The Old is a reference to the fact that the members of it had to have seen many military campaigns.

It was the 1er who formed two squares, one of them containing the Emperor himself, both squares marched from the battlefield, fending off enemy cavarly pursuits at the same time.

Battle Honours: Battle Honours: 1815 Model Flags:

Marengo 1800

Ulm 1805

Austerlitz 1805

Jena 1806

Eylau 1807

Friedland 1807

Ekmull 1809

Essling 1809

Wagram 1809

Smolensk 1812

Borodino 1812

Vienna, Berlin, Madrid and Moscow

Battle of Waterloo:

The drums of the 1st Grenadier Regiment beat the "Grenadiers" to call stray veterans, who gradually filled to the brim their squares that were already crammed with marshals, generals, and officers: Marshal Soult, Marshal Ney, General Bertrand, General Drouot, General Petit and others. The possibility of Prussian cavalry attack caused the 1st Grenadier Regiment (the oldest of the Old Guard) to form up in two squares, not far stood the house of the guide Decoster.

The square that was closer to the enemy, sent out its skirmishers who soon were "heavily engaged" against Prussian skirmishers. In other square, strengthened by a battery of 6 6pdr guns, Guard sappers and Guard sailors, was Napoleon.

The two squares left the battlefield with their characteristic bull-dog obstinacy. One square marched on the paved road and the other across the fields. Both moved in perfect order despite Prussian and British pursuit. The Guard battery was firing methodically, but it stopped neither the enemy nor the fugitives.

Mjr. Howard with the British 10th Hussars received order to charge one of the squares. The Old Guard stood fast, the British received a volley and dispersed before coming into any contact with it.

Howard took a musket ball in the face and fell from his charger. A veteran stepped out from the ranks and bashed in Howard's skull with the butt of his musket.

The British dragoons were next to charge.

The messenger of this order, Dawson, confessed that he would never forget the looks on their faces when he communicated these orders to them. The dragoons advanced but not too fast, and obviously without much enthusiasm. The Old Guard fired, Dawson was knocked off his horse, the British made a full turn and fled.

Jena: The 1er held the center of the French line

During the retreat of 1812 Napoleon ordered The Imperial Guard, including 1er to hold back the Russians to buy the army time to retreat: At 5:00 a.m., 11,000 Imperial Guardsman marched out of Krasny intending to secure the terrain immediately east and southeast of the town.[25] These troops split into two columns: one 5,000 strong moving along the road to Smolensk, the other 6,000 Young Guardsmen led by Roguet, marching south of the road toward Uvarovo.[26] The left flank of the Young Guard's column was protected by a battalion of elite Old Guard grenadiers, described by Segur as forming a "fortress like square."[27] Stationed on the right of these columns were the weak remnants of the Guard's cavalry.[27] Overall direction of the operation was entrusted to Marshal Mortier.[28]

This bold, unexpected feint of the Guard was lent additional melodrama by the personal presence of Napoleon. With his birch bark walking stick in hand, Napoleon placed himself at the helm of his Old Guard grenadiers, declaring "I have played the Emperor long enough! It is time to play general!"[29]

Facing the tattered but resolute Imperial Guardsmen were densely concentrated Russian infantry columns to the south and east, supported by massive, powerful artillery batteries.

Lacking sufficient cannon of their own, the Guardsmen were badly outgunned by the enemy. As described by Segur: "Russian battalions and batteries barred the horizon on all three sides—in front, on our right, and behind us"[27]

Kutusov's reaction to the Imperial Guard's forward movement led to the most decisive and controversial development of the battle: he promptly cancelled his army's planned offensive, even in spite of the Russians' overwhelming superiority in strength.[30]

For most of the rest of this day, the Russians remained at a safe distance from the Guard, beyond the reach of French muskets and bayonets, and simply blasted the enemy with cannonfire from afar.

Around 11:00 a.m., as the Imperial Guard was holding firm near Uvarovo despite its withering losses, Napoleon received intelligence reports that Tormasov's troops were readying to march west of Krasny.[34] This news, coupled with the Young Guard's mounting casualties, forced Napoleon to abandon his ultimate object of standing down Kutusov long enough for Ney's III Corps to arrive in Krasny. If Kutusov opted to attack, the Grande Armée would be encircled and destroyed. Napoleon immediately ordered the Old Guard to fall back on Krasny, and then join Eugène's IV Corps in marching west toward Liady and Orsha. The Young Guard, nearing its breaking point, would remain near Uvarovo, to be relieved shortly thereafter by Davout's reorganized troops from Krasny.

Battle of Lutzen: Wittgenstein and Blücher took the bait, continuing to press Ney until they ran into the "hook" Napoleon had prepared. Once their advance had halted, with the perfect timing of old, he struck. While he had been reinforcing Ney, he had also concentrated a great mass of artillery (Grande Batterie) that unleashed a devastating barrage towards Wittgenstein's center. Then Napoleon himself, along with his Imperial Guard, led the massive counter assault into the allied flank.

Us at the battle of Hanau:

MacDonald's Corps and the Guard were to penetrate into the Lamboi forest.

Three hours later Grenadiers of the Old Guard had cleared the area of allied troops, and Drouot began to deploy 50 cannons supported by cavalry of the Guard and Sébastiani.

Battle of Montmirail: From the central position, the French then drove west with the only available troops, the Old Guard and a division of the "Marie Louise" (Young Guard), in hopes of smashing Blucher’s leading elements (Sacken and Yorck) in isolation and with their backs to the French held bridges over the Marne.

Battle of Laon: Marmont was saved by Colonel Charles Nicolas Fabvier, who returned on his own initiative with 1,000 troops to clear the road, and by 125 veterans of the Old Guard, who repelled the Allied cavalry trying to block the French from escaping.

Information gathered by Tambour Bloodreaver, Caporal Quintillius and Adjutant Chef Mr T

There were in that Division 3 grenadier regiments, and 2 chasseur regiments.

As we all know, this is how a regular grenadier looks.

If you´ve noticed there is a white embroidered grenade, on the top of their cap. That first became official in 1807 after the peace in Tilsit where it before was a white cross.

After Napoleon abdicated in 1814, and Louis the XVIII was restored, he replaced the grenadiers eagle with a royal plate. When Napoleon returned for his 100 days, they didn´t have time to replace it, so they put a tricolor on it. So basiclly we didn´t have the eagle plate at waterloo.

Here you see a picture of a grenadier with a normal hat on instead of the "Bonnet de Poil" (bearskin hat). The guard may have been proud of it, but marching with it was horrible, so they used that hat instead when they weren´t at ceremonies or in battle.

The Grenadiers would usually be on the march with full equipment, which would be around 32 pounds. Sometimes they would be ordered to march over 140 to 180 km in 36 to 76 hours.

A linesmen once made the remark: "Emperor is using our legs more than our bayonets to make war."

However, out of "fatherly love" towards his children´s favorite, the Emperor had put carts avalible to transport his grenadiers, while the other line regiment had to walk.

Typically, Colonels of any regiment within the Old Guard could have the rank of "Brigadier General". Like you see above.

The 1er Grenadiers musicians were not in green jackets, like you see in Mount&Musket, they were wearing standard uniforms with golden trimmed robes and fine bronze plates on their shoulders.

The 1er Grenadiers were part of Napoleon's Imperial Guard (which was an army in itself, having cavalry, artillery and infantry at its peak), which was in turn part of Napoleon's Grande Armee, the massive fighting force Napoleon used to smash Europe, which ultimately was mostly killed in the snows of Russia. Unfortunately, almost all of the initial Old Guard were dead by the time Napoleon had retreated from Russia.

The 1er Grenadiers, I'm sure you all know, were known as Les Grognards (the grumblers), reputed to air any complaints they had to their commanders without any hesitation. The most common grumble they would have is that they were not committed to battle enough, only being committed when there was dire need for it. Other regiments in the guard were committed at times, but the treasured 1er saw little action. However, attributed to the action the Old Guard did see, was the fact that they were reputedly undefeated. The Guard was far from useless however, in fact saving Napoleon's life at one point, when he was surrounded in a church at the Battle of Eylau, with only his advisers to defend him! They managed to hold out for long enough against the Russians before some battalions of the Guard arrived to drive them off.

The 1er Grenadiers and 1er Chasseurs were the best selection of men by far of the Old Guard, and people may say that the Old Guard routed at Waterloo, and call us cowards, but it was the rest of the Imperial Guard that infamously routed, a few battalions of surviving Old Guard -the 1er being part of them- standing their ground.

Also, it is true that the Old Guard were not that old, you actually HAD to be under 35 to join it! The Old is a reference to the fact that the members of it had to have seen many military campaigns.

It was the 1er who formed two squares, one of them containing the Emperor himself, both squares marched from the battlefield, fending off enemy cavarly pursuits at the same time.

Battle Honours: Battle Honours: 1815 Model Flags:

Marengo 1800

Ulm 1805

Austerlitz 1805

Jena 1806

Eylau 1807

Friedland 1807

Ekmull 1809

Essling 1809

Wagram 1809

Smolensk 1812

Borodino 1812

Vienna, Berlin, Madrid and Moscow

Battle of Waterloo:

The drums of the 1st Grenadier Regiment beat the "Grenadiers" to call stray veterans, who gradually filled to the brim their squares that were already crammed with marshals, generals, and officers: Marshal Soult, Marshal Ney, General Bertrand, General Drouot, General Petit and others. The possibility of Prussian cavalry attack caused the 1st Grenadier Regiment (the oldest of the Old Guard) to form up in two squares, not far stood the house of the guide Decoster.

The square that was closer to the enemy, sent out its skirmishers who soon were "heavily engaged" against Prussian skirmishers. In other square, strengthened by a battery of 6 6pdr guns, Guard sappers and Guard sailors, was Napoleon.

The two squares left the battlefield with their characteristic bull-dog obstinacy. One square marched on the paved road and the other across the fields. Both moved in perfect order despite Prussian and British pursuit. The Guard battery was firing methodically, but it stopped neither the enemy nor the fugitives.

Mjr. Howard with the British 10th Hussars received order to charge one of the squares. The Old Guard stood fast, the British received a volley and dispersed before coming into any contact with it.

Howard took a musket ball in the face and fell from his charger. A veteran stepped out from the ranks and bashed in Howard's skull with the butt of his musket.

The British dragoons were next to charge.

The messenger of this order, Dawson, confessed that he would never forget the looks on their faces when he communicated these orders to them. The dragoons advanced but not too fast, and obviously without much enthusiasm. The Old Guard fired, Dawson was knocked off his horse, the British made a full turn and fled.

Jena: The 1er held the center of the French line

During the retreat of 1812 Napoleon ordered The Imperial Guard, including 1er to hold back the Russians to buy the army time to retreat: At 5:00 a.m., 11,000 Imperial Guardsman marched out of Krasny intending to secure the terrain immediately east and southeast of the town.[25] These troops split into two columns: one 5,000 strong moving along the road to Smolensk, the other 6,000 Young Guardsmen led by Roguet, marching south of the road toward Uvarovo.[26] The left flank of the Young Guard's column was protected by a battalion of elite Old Guard grenadiers, described by Segur as forming a "fortress like square."[27] Stationed on the right of these columns were the weak remnants of the Guard's cavalry.[27] Overall direction of the operation was entrusted to Marshal Mortier.[28]

This bold, unexpected feint of the Guard was lent additional melodrama by the personal presence of Napoleon. With his birch bark walking stick in hand, Napoleon placed himself at the helm of his Old Guard grenadiers, declaring "I have played the Emperor long enough! It is time to play general!"[29]

Facing the tattered but resolute Imperial Guardsmen were densely concentrated Russian infantry columns to the south and east, supported by massive, powerful artillery batteries.

Lacking sufficient cannon of their own, the Guardsmen were badly outgunned by the enemy. As described by Segur: "Russian battalions and batteries barred the horizon on all three sides—in front, on our right, and behind us"[27]

Kutusov's reaction to the Imperial Guard's forward movement led to the most decisive and controversial development of the battle: he promptly cancelled his army's planned offensive, even in spite of the Russians' overwhelming superiority in strength.[30]

For most of the rest of this day, the Russians remained at a safe distance from the Guard, beyond the reach of French muskets and bayonets, and simply blasted the enemy with cannonfire from afar.

Around 11:00 a.m., as the Imperial Guard was holding firm near Uvarovo despite its withering losses, Napoleon received intelligence reports that Tormasov's troops were readying to march west of Krasny.[34] This news, coupled with the Young Guard's mounting casualties, forced Napoleon to abandon his ultimate object of standing down Kutusov long enough for Ney's III Corps to arrive in Krasny. If Kutusov opted to attack, the Grande Armée would be encircled and destroyed. Napoleon immediately ordered the Old Guard to fall back on Krasny, and then join Eugène's IV Corps in marching west toward Liady and Orsha. The Young Guard, nearing its breaking point, would remain near Uvarovo, to be relieved shortly thereafter by Davout's reorganized troops from Krasny.

Battle of Lutzen: Wittgenstein and Blücher took the bait, continuing to press Ney until they ran into the "hook" Napoleon had prepared. Once their advance had halted, with the perfect timing of old, he struck. While he had been reinforcing Ney, he had also concentrated a great mass of artillery (Grande Batterie) that unleashed a devastating barrage towards Wittgenstein's center. Then Napoleon himself, along with his Imperial Guard, led the massive counter assault into the allied flank.

Us at the battle of Hanau:

MacDonald's Corps and the Guard were to penetrate into the Lamboi forest.

Three hours later Grenadiers of the Old Guard had cleared the area of allied troops, and Drouot began to deploy 50 cannons supported by cavalry of the Guard and Sébastiani.

Battle of Montmirail: From the central position, the French then drove west with the only available troops, the Old Guard and a division of the "Marie Louise" (Young Guard), in hopes of smashing Blucher’s leading elements (Sacken and Yorck) in isolation and with their backs to the French held bridges over the Marne.

Battle of Laon: Marmont was saved by Colonel Charles Nicolas Fabvier, who returned on his own initiative with 1,000 troops to clear the road, and by 125 veterans of the Old Guard, who repelled the Allied cavalry trying to block the French from escaping.

Information gathered by Tambour Bloodreaver, Caporal Quintillius and Adjutant Chef Mr T

History; The 92nd Gordon Highlanders at Quatre Bras and the death of the gallant John Cameron of Fassifern

The Brunswickers had been stationed near the 92nd, and about four o’clock the Duke of Brunswick led his hussars past the 92nd, to repel some French cavalry who had broken the Brunswick Infantry; the hussars charged gallantly, but were disorganised by musketry fire. The Duke was mortally wounded, and they fled before the Red Lancers and Light Cavalry, who were soon up with them, “cutting them down most horribly.” Wellington, who was in front when the hussars charged, was carried away in their flight, and in danger of being taken; he galloped to the bank lined by the 92nd, and calling to them to lie still, rode at the fence and jumped it, men and all. He had his sword drawn, and as soon as the Highlanders were between him and his pursuers, he turned round with a confident smile, and ordered the regiment to be ready. The flying Brunswickers passed round the right flank close to the bayonets; the French mingled with them, cutting and slashing. As soon as the Brunswickers had cleared their right, the Grenadier Company wheeled back on the road; the rest were to fire obliquely on the mass of rapidly advancing cavalry, who, elated at their success, charged them. The Highlanders received them as they did the cuirassiers, with a volley at close quarters.

Two hundred yards from the hamlet was a two-storeyed house beside the road, and from its rear ran a thick hedge a short way across a field. On the opposite side of the road was a garden surrounded by a thick hedge. Under cover of a cannonade, two columns of French infantry were now seen advancing, one by the Charleroi road, the other by a hollow in front of the wood of Bossu. The house and hedge were occupied by these troops, while some advanced still nearer to the 92nd, and the main body, 1200 to 1500 strong, took post about a hundred yards in rear of the garden. The colonel’s fiery temper chafed to be at them, as he paced impatiently up and down, and he asked leave to charge. “Take your time, Cameron, you’ll get your fill of it before night,” said the Duke, who was again with the regiment, for their position commanded a general view. Soon he said, “Now, 92nd, you must charge these two columns of infantry!” Instantly the regiment, about 600 in number, leaped over the ditch, headed by Colonel Cameron and General Barnes, the latter calling out, “Come on, my old 92nd!”—for their old brigadier loved the regiment, and though it was not his duty to charge, “he could not resist the impulse,” writes a 92nd officer. The Grenadiers and First Company took the high road, the other companies to their right advanced upon the house and hedge, and some upon the garden, the enemy pouring a deadly fire on them from the windows and from the hedge. The officer with the regimental colour was shot through the heart, the staff of the colour was shattered in six pieces by three balls, and the staff of the king’s colour by one. Cameron was struck in the groin by a shot fired from an upper window; he lost command of his horse, the animal galloped back to where the colonel’s groom was standing with his second horse. There it suddenly stopped, and its rider was pitched on his head on the road.

And Sunart rough and wild Ardgour,

And Morven long shall tell

And proud Ben Nevis hear with awe,

How, upon bloody Quatre-Bras,

Brave Cameron heard the wild hurrah

Of conquest as he fell.

At the house the bayonet did its deadly work, and Colonel Cameron was amply avenged by his infuriated followers, but the main body beyond showed no disposition to retire; they were greatly superior in numbers, and kept up a shower of musketry upon the Highlanders at the hedge, sufficient to appal any but the most experienced soldiers; and but for the officers’ attention to their duty, and the encouragement of their veteran comrades, some of the younger men would not have been kept steady under it. Lieut.-Colonel Mitchell, who had succeeded Cameron, was wounded, and Major Donald MacDonald took command. To extricate themselves from this situation part of the battalion was moved round the right side of the house and garden, and part round the left, while a third passed through the garden and forced the gates under a fire described by an officer of the party as “truly dreadful,” and which they could not answer effectively till the whole battalion could be brought to bear upon the enemy. Then the word was given-the thrilling British cheer, which none can hear unmoved, rang out as they levelled their bayonets to the charge. For a few seconds the French awaited the assault, but as they marked the steadfast bearing and stern countenances of the rapidly-approaching Highlanders, their courage failed them, they gave way, and sought to escape by the hollow up which their left column had advanced. As soon as they turned their backs, the 92nd plied them with musketry; “And so well did our lads do their duty, that at every step we found a dead or wounded Frenchman.” “Never was the fire of a body of men given with finer effect than that of the 92nd during the pursuit, which continued for fully half a mile.” Being completely separated from the rest of the line, and threatened by a corps of cavalry, the regiment entered the wood and maintained their position there against all comers till relieved by the Guards, and about eight o’clock they were ordered to retire, and form behind the houses at Quatre-Bras. A night under arms, an eighteen miles’ march, and five hours’ fighting is hungry work; the Highlanders cooked their suppers in the cuirasses worn by the cuirassiers they had killed a few hours before.

Two hundred yards from the hamlet was a two-storeyed house beside the road, and from its rear ran a thick hedge a short way across a field. On the opposite side of the road was a garden surrounded by a thick hedge. Under cover of a cannonade, two columns of French infantry were now seen advancing, one by the Charleroi road, the other by a hollow in front of the wood of Bossu. The house and hedge were occupied by these troops, while some advanced still nearer to the 92nd, and the main body, 1200 to 1500 strong, took post about a hundred yards in rear of the garden. The colonel’s fiery temper chafed to be at them, as he paced impatiently up and down, and he asked leave to charge. “Take your time, Cameron, you’ll get your fill of it before night,” said the Duke, who was again with the regiment, for their position commanded a general view. Soon he said, “Now, 92nd, you must charge these two columns of infantry!” Instantly the regiment, about 600 in number, leaped over the ditch, headed by Colonel Cameron and General Barnes, the latter calling out, “Come on, my old 92nd!”—for their old brigadier loved the regiment, and though it was not his duty to charge, “he could not resist the impulse,” writes a 92nd officer. The Grenadiers and First Company took the high road, the other companies to their right advanced upon the house and hedge, and some upon the garden, the enemy pouring a deadly fire on them from the windows and from the hedge. The officer with the regimental colour was shot through the heart, the staff of the colour was shattered in six pieces by three balls, and the staff of the king’s colour by one. Cameron was struck in the groin by a shot fired from an upper window; he lost command of his horse, the animal galloped back to where the colonel’s groom was standing with his second horse. There it suddenly stopped, and its rider was pitched on his head on the road.

And Sunart rough and wild Ardgour,

And Morven long shall tell

And proud Ben Nevis hear with awe,

How, upon bloody Quatre-Bras,

Brave Cameron heard the wild hurrah

Of conquest as he fell.

At the house the bayonet did its deadly work, and Colonel Cameron was amply avenged by his infuriated followers, but the main body beyond showed no disposition to retire; they were greatly superior in numbers, and kept up a shower of musketry upon the Highlanders at the hedge, sufficient to appal any but the most experienced soldiers; and but for the officers’ attention to their duty, and the encouragement of their veteran comrades, some of the younger men would not have been kept steady under it. Lieut.-Colonel Mitchell, who had succeeded Cameron, was wounded, and Major Donald MacDonald took command. To extricate themselves from this situation part of the battalion was moved round the right side of the house and garden, and part round the left, while a third passed through the garden and forced the gates under a fire described by an officer of the party as “truly dreadful,” and which they could not answer effectively till the whole battalion could be brought to bear upon the enemy. Then the word was given-the thrilling British cheer, which none can hear unmoved, rang out as they levelled their bayonets to the charge. For a few seconds the French awaited the assault, but as they marked the steadfast bearing and stern countenances of the rapidly-approaching Highlanders, their courage failed them, they gave way, and sought to escape by the hollow up which their left column had advanced. As soon as they turned their backs, the 92nd plied them with musketry; “And so well did our lads do their duty, that at every step we found a dead or wounded Frenchman.” “Never was the fire of a body of men given with finer effect than that of the 92nd during the pursuit, which continued for fully half a mile.” Being completely separated from the rest of the line, and threatened by a corps of cavalry, the regiment entered the wood and maintained their position there against all comers till relieved by the Guards, and about eight o’clock they were ordered to retire, and form behind the houses at Quatre-Bras. A night under arms, an eighteen miles’ march, and five hours’ fighting is hungry work; the Highlanders cooked their suppers in the cuirasses worn by the cuirassiers they had killed a few hours before.

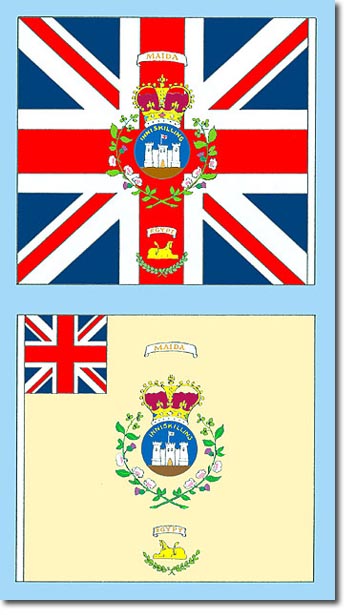

27th (Enniskillen) Regiment of Foot

"The Skins"

Written by Lordnred from his own personal Research on the Internet, in books, and of course at the Regimental Museum in Enniskillen:

The Regiment was formed in 1688 by Colonel Zachariah Tiffin to defend Enniskillen (County Fermanagh, Ireland (Present Day Northern Ireland) from the Jacobite army during the Williamite wars in Ireland along with a regiment of Dragoons which later became the 6th (Enniskillen) Dragoons and are currently part of the Royal Dragoon Guards (I shall write no more of them in this as this history concerns the foot Regiment). At this time, regiments were not numbered, but named after their colonel, so the regiment was called Colonel Tiffin's Regiment. The Regiment was more of a militia at this time and made expeditions out into the surrounding Area to fight the Jacobites of King James, including the Battle of Newtownbutler (sometimes called the Battle of Enniskillen). So succesful were these expeditions that the regiment (And the Dragoons) were incorporated into the Army of King William the Third. After this it fought in the famous Battle of the Boyne (1690).

It was next stationed in the Low Countries (the Netherlands), where it was present at the Siege of Namur (1695.) During the next 50 years it served in places such as Minorca, Spain and the West Indies. It took part in the Battles of Falkirk and Culloden During the Jacobite Rising of 1745. In 1751, regiments began to be numbered, and the Enniskillen regiment became the 27th (Enniskillen) Regiment of Foot. "Enniskillen" was the oldest territorial title in the line infantry of the British army. During the Seven Years War (1756-63) the regiment fought in North America and the west Indies against the French. In 1778 the regiment was again sent to fight in the American Revolutionary War, where it fought in the West Indies against the French, who had an Alliance with the Americans. The war against the French came to an End in 1783.

In 1793 the French Revolutionary Wars broke out. In 1796 the Regiment took part in the Battle/Siege of St Lucia where its colours were displayed on the flagstaff there for an Hour before a Union flag was put up. This had never before, or since happened to a regiment.The regiment then fought in the Low Countries (again, the Netherlands) and Egypt where it took part in the Battle of Alexandria (1801), The second battalion was in the Garrison of that city after the battle.The First Battalion Distinguished itself at Maida in Italy (1806.) The 2nd and 3rd Battalions took part in the Penninsular war in such battles as Badajoz (1812), Salamanca (1812), Vitoria (1813), Pyrenees (1813), Nivelle (1813, Again), Orthez (1814), and Toulouse (1814.)

The Regiment's First Battalion (the one We Represent) was the only Irish regiment/Battalion Present at Waterloo (1815) The battalion started the day with 698 men and Officers and ended with 103 killed and 373 wounded. The Regiment was stated by Wellington to have saved the centre of his line. Between 1837 and 1847 the regiment fought in several Native wars in South Africa.In 1840 the spelling of Enniskillen in the Regiments name was Changed to Inniskilling (archaic Spelling). The Regiment served in India between 1854 and 1868 where it was involved in Supressing the Indian Mutiny and Keeping law and order in North-West India.

In 1881 the regiment was Amalgamated with the 108th Regiment of Foot to become the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers. This regiment fought in the Second Boer war, the Tirah campaign of 1897 in India, The First World War, the Second World War (They Fought in Burma, Tunisia, and Italy, Among other places.), Malaya, and Kenya. In 1968 the Regiment was amalgamated with the Royal Ulster Rifles and the Royal Irish Fusiliers to become the Royal Irish Rangers, which served in places like Bosnia and Northern Ireland. In 1992 the Regiment was Amalgamated again with the Ulster Defence Regiment to become the Royal Irish Regiment (27th (Inniskilling) 83rd and 87th and Ulster Defence Regiment). The Royal Irish served recently Iraq and Afganistan.

This Brings the regiment up to the Present day.

It was next stationed in the Low Countries (the Netherlands), where it was present at the Siege of Namur (1695.) During the next 50 years it served in places such as Minorca, Spain and the West Indies. It took part in the Battles of Falkirk and Culloden During the Jacobite Rising of 1745. In 1751, regiments began to be numbered, and the Enniskillen regiment became the 27th (Enniskillen) Regiment of Foot. "Enniskillen" was the oldest territorial title in the line infantry of the British army. During the Seven Years War (1756-63) the regiment fought in North America and the west Indies against the French. In 1778 the regiment was again sent to fight in the American Revolutionary War, where it fought in the West Indies against the French, who had an Alliance with the Americans. The war against the French came to an End in 1783.

In 1793 the French Revolutionary Wars broke out. In 1796 the Regiment took part in the Battle/Siege of St Lucia where its colours were displayed on the flagstaff there for an Hour before a Union flag was put up. This had never before, or since happened to a regiment.The regiment then fought in the Low Countries (again, the Netherlands) and Egypt where it took part in the Battle of Alexandria (1801), The second battalion was in the Garrison of that city after the battle.The First Battalion Distinguished itself at Maida in Italy (1806.) The 2nd and 3rd Battalions took part in the Penninsular war in such battles as Badajoz (1812), Salamanca (1812), Vitoria (1813), Pyrenees (1813), Nivelle (1813, Again), Orthez (1814), and Toulouse (1814.)

The Regiment's First Battalion (the one We Represent) was the only Irish regiment/Battalion Present at Waterloo (1815) The battalion started the day with 698 men and Officers and ended with 103 killed and 373 wounded. The Regiment was stated by Wellington to have saved the centre of his line. Between 1837 and 1847 the regiment fought in several Native wars in South Africa.In 1840 the spelling of Enniskillen in the Regiments name was Changed to Inniskilling (archaic Spelling). The Regiment served in India between 1854 and 1868 where it was involved in Supressing the Indian Mutiny and Keeping law and order in North-West India.

In 1881 the regiment was Amalgamated with the 108th Regiment of Foot to become the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers. This regiment fought in the Second Boer war, the Tirah campaign of 1897 in India, The First World War, the Second World War (They Fought in Burma, Tunisia, and Italy, Among other places.), Malaya, and Kenya. In 1968 the Regiment was amalgamated with the Royal Ulster Rifles and the Royal Irish Fusiliers to become the Royal Irish Rangers, which served in places like Bosnia and Northern Ireland. In 1992 the Regiment was Amalgamated again with the Ulster Defence Regiment to become the Royal Irish Regiment (27th (Inniskilling) 83rd and 87th and Ulster Defence Regiment). The Royal Irish served recently Iraq and Afganistan.

This Brings the regiment up to the Present day.

Follow the same format, and I hope to see some interesting info on other reg's

Remember: Keep it short, sweet, and provide a battle or two if you can. Don't post anything about recruiting though, let's keep this totally historical.

If you feel like there is another regiment you want to post about, but it isn't an actual regiment in the community, that's also fine. Just provide some info

I'll be organizing a list as more regiments post.